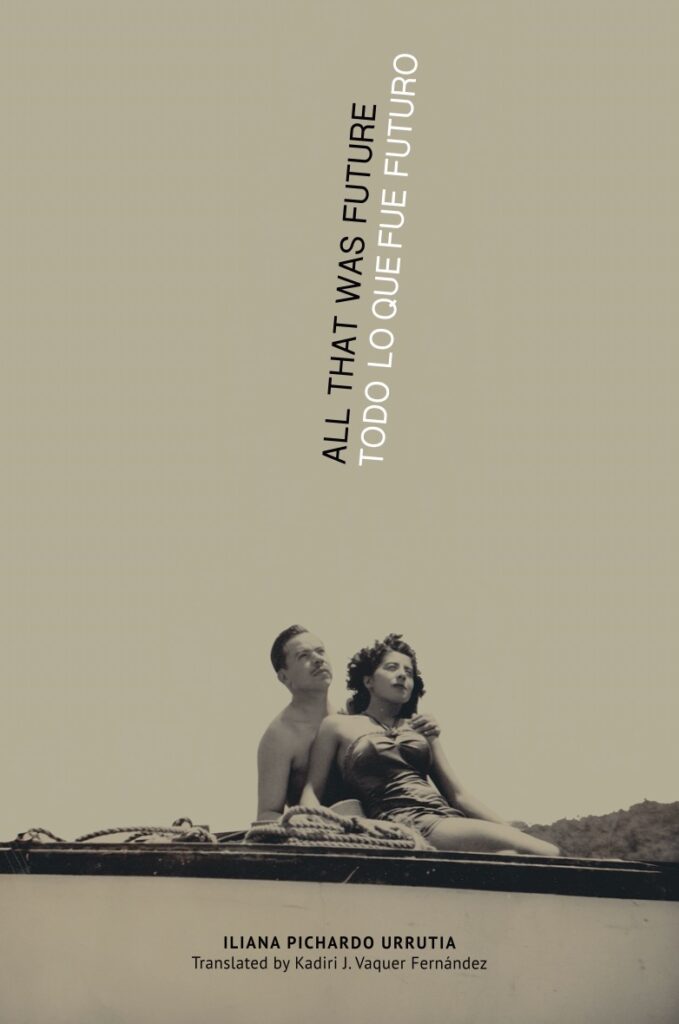

Iliana Pichardo Urrutia’s poetry collection, All That Was Future, is an ethereal embrace with the dead. The book was written in Spanish, though an English translation, by Kadiri J. Vaquer Fernández, accompanies each piece on the left side. Whether you’re familiar with Dia de Muertos and its traditions, these poems offer a recipe for erecting an altar within a heart.

I sat down with the author and documentary filmmaker to hash out her encounters with death.

Juania

The speaker in All That Was Future is constantly weaving this thread between life, this realm, and something else, death, a “vortex.” I was struck by the opening sentence in “8: Damages to the Nation” “Sometimes, you land in hell by car…” Do you experience this jostle between the mundane and this other unseen place in your waking life? How or when did this kind of sewing surface in the book?

Iliana

The idea for this book came to me many years ago while traveling through the southern part of the continent. In the distance and solitude, I began to trace the turning points of my life: moments when I experienced metaphorical deaths. They might have been simple things, moments that dissolved into time, yet they left a mark on my body and on my understanding that from that moment on, something new was being born.

So I began writing poems to those deaths of mine; this idea has been present since the book’s conception. I have always been fascinated by the idea of death. As a child, I felt an absolute terror of total dissolution. Now I’m amazed at how, in our daily lives, we forget that everything is dying a little each day, even the things we try to freeze in time, even memory, even archives, everything deteriorates.

I think I try to remain aware of this—or to remind myself of it—not in a pessimistic way, but in an effort to find, within this certainty, a sense of wonder at what is greater than my own personal story. When I am no longer here, the world will keep rolling beneath my children’s feet.

Juania

Altares hold material things, and there’s certainly a focus on some of those in these poems. Even so, there was this sensation I kept having while reading your book…this shrinking, a being whittled down to inanimate things we form attachments to, but I also felt this freedom, a reemergence when there’d be these moments of transcending our vessels–the body! I witnessed this link, these sacred connections to nature (e.g. lungs to blue wings, a girl’s body to a chrysalis)–but only in likeness, en algo mas. There’s a poem in particular that stands out in which the speaker finds her grandmother’s empty house and accepts her permanent absence, realizing what does remain: “only the foam / of her name / on the coasts / of your body.” Do you believe our body carries this beyondness while we’re still living, or does nature hold it and we sometimes catch a glimpse of it?

Iliana

The idea of the altars came from a prompt in my poetry class during the MFA at UTEP, with my professor Kadiri J. Vaquer Fernández, who also translated the book and to whom I am deeply grateful. From that prompt, I began to conceive the poems as altars. Through the poetic gesture, the intention was to create a kind of offering, homage, or remembrance of those moments when something shifted or transformed in me. Naturally, certain objects and photos also appear. I think of them as the archaeology of a life. And, in the same way, the body is also present. I do believe, as you mentioned, that our bodies carry this beyondness even while we’re still alive. The body remembers everything, it holds memory. From the primordial sea we come from, within our mother’s body, to the cellular memory passed down from our grandmothers’ bodies, which already carried us.

Juania

Thinking of what the body carries, there’s certainly a focus on matrilineage in the poems. Your poem “1: The Expulsion” unravels this idea that our mothers are our “Big Bang.” While reading this, I fell into the divinity, the sublime and the violence of our origin: “To die is to open eyes in the snow, the first time the body is held outside the amniotic fluid…when the mother is a surface, an eye that names you for the first time…” What do you make of this jarring introduction to the earth–that is not only violent for the baby, but of course, also for the mother? Why is our first interaction with our mothers wrapped up in injury?

Iliana

In the book, I explore not only the fragility of the body, but also the strength it carries. In terms of matrilineage, ever since my first miscarriage, I’ve been struck by the idea that the body can hold the potential to create life, but also the contrary. This connects, for me, to the sea, a recurring element in my writing, because of its movement, and because the first time I saw a uterine ultrasound, it looked to me like the sea. The sea with all its force and violence, but also in its calmer state, like a reef full of life.

I don’t know if it’s injury, that first interaction with the world, but it’s definitely a sudden shift of state, from an element like water, to another where the baby must breathe on their own. In the same way, the woman’s body is never the same. The being that once was inside is now outside, even though for the first few months, it still carries the imprint of being one. In the poem you mentioned, I speak about being born with a death sentence, not in a negative way, but in the sense I spoke of earlier, the impermanence we so often forget. I reflect on my own birth, and in other poems, I write about being on the other side, giving life.

Juania

Most poetry is full of the dreadful “I” but your entire book is written in the second person–unless it’s describing another, then it’s in the third. It had an intoxicating effect on me, in the best way! How did this choice change the relationship between the poetry/the speaker, and the reader?

Iliana

From the very beginning, when I first conceived this book, I wrote all the poems in the second person. Since each poem is an altar to one of the metaphorical deaths of my former selves, I am addressing mis muertas, those past versions of me who have died in some way. That’s why I chose the second person. This shift away from the “I” allowed me to create different personas, and to speak to myself with a certain distance. I also understand that the second person directly addresses the reader, so perhaps, even if unintentionally, the reader also feels implicated, or drawn into reflecting on their own turning-point moments. That’s something I would hope for.

Juania

You’re a documentary filmmaker; how is the experience of documenting reality through a camera different from recounting it through poetry for you?

Iliana

Both documentary filmmaking and poetry have their own language, their own craft. But I really enjoy working with both. I’m especially drawn to archives: photographic, filmic, and written, and to thinking about how they can be intervened to create new meanings. I also deeply enjoy people’s stories and documenting their voices. I often try to bring elements of poetic language into my filmmaking, and one of my favorite subgenres of poetry is documentary poetry, which allows me to incorporate research and other techniques into my writing. For me, the two forms speak to each other. My approach to poetry, as well as to documentary, is about de-automatizing perception, trying to engage with “reality” from a different perspective, one that is more sensory, so that the person reading, listening, or watching can feel the experience in their own body. Lidia Yuknavitch says, “poetic language is probably the closest we bring language to experience.” I believe that, too. Through image, sound, rhythm, and sensation, we can invite others to truly inhabit an experience.

All That Was Future is available for purchase here.