“A 1946 National Magazine article described a Chicago building where the landlord had divided a 540 square foot storefront into six cubicles, each housing a family. He had similarly subdivided the second story. Total monthly rent was as great as that generated by a luxury apartment on Chicago’s Gold Coast along Lake Michigan.”1

Houston is a series of grids: streets, buildings, shopping malls, the electricity illuminating their contents and the blueprints that envisioned them all. H-Town lacks governance regarding land use (except in rare cases, most which benefit the affluent through deed restrictions). The emptiness of the squares on these urban grids have always been conduits for the Houstonian imagination. I’ve lived in an apartment complex that had a movie theater, several restaurants, a gas station, food trucks, auto repair garages, a bar, a laundromat, a sex shop, and three elementary-age schools within a five-minute walking radius of a predominantly Black & Brown block.

*

One of Modern Art’s distinguishing factors, according to Rosalind Krauss, is the presence of grids. The grid permeates the nature of contemporary American consciousness and urban design. However, in the context of white art, the grid itself is a diagrammed white space that prioritizes white aesthetics since white humanity is inherently valued in Western society. For POC, the grid itself is a mechanism of oppression to be seized and either abolished or decolonized, like a prison or urban planning that places resources outside neighborhoods of color.

The most transformative use of grids has been through work subverting the grid’s utilitarian purpose by utilizing the form to serve POC aesthetics. It’s no coincidence that five artists of color in Houston explicitly utilize grids in their work: Matt Manalo, Angel Lartigue, Irene Antonia Diane Reece, Marcos Hernandez Chavez, and Jessica Gonzalez.

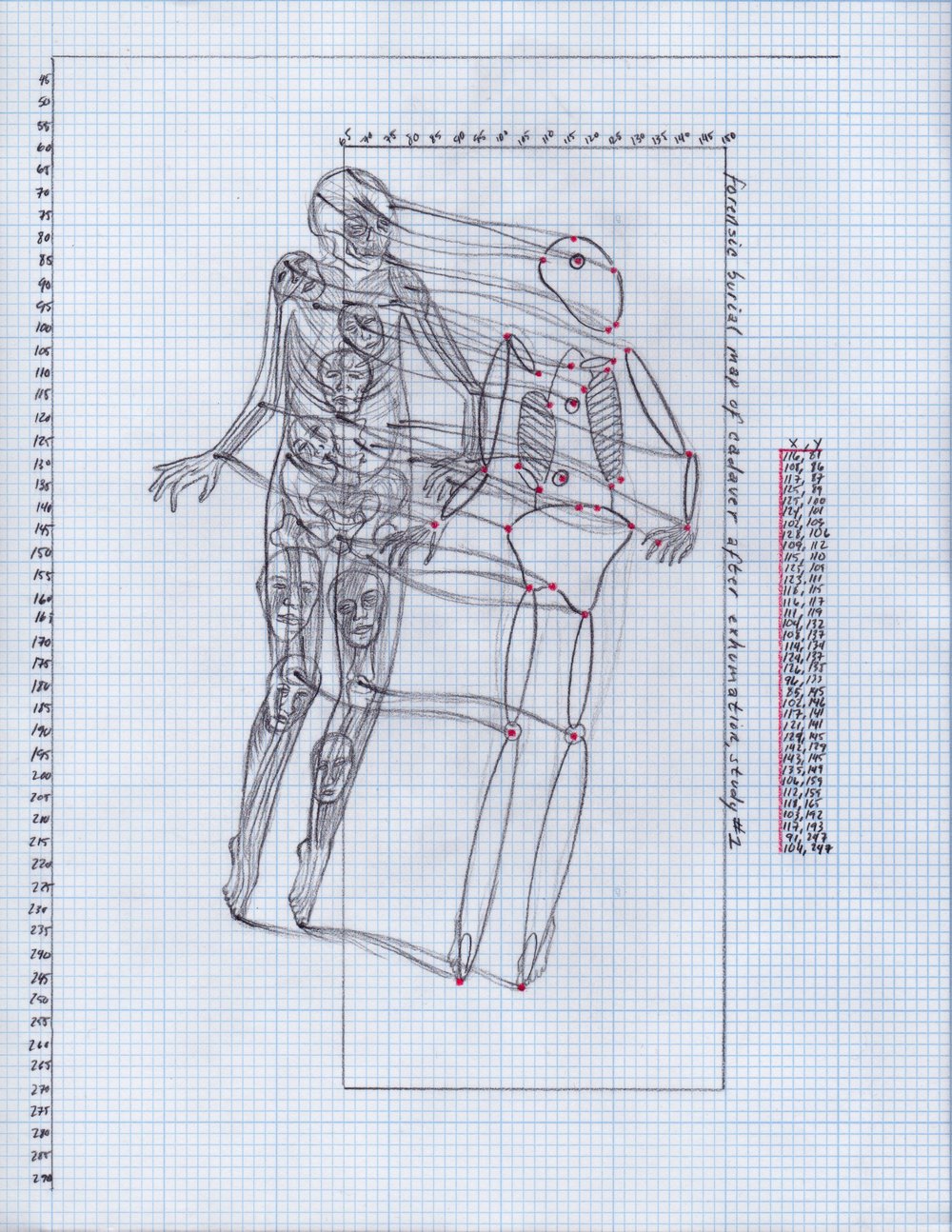

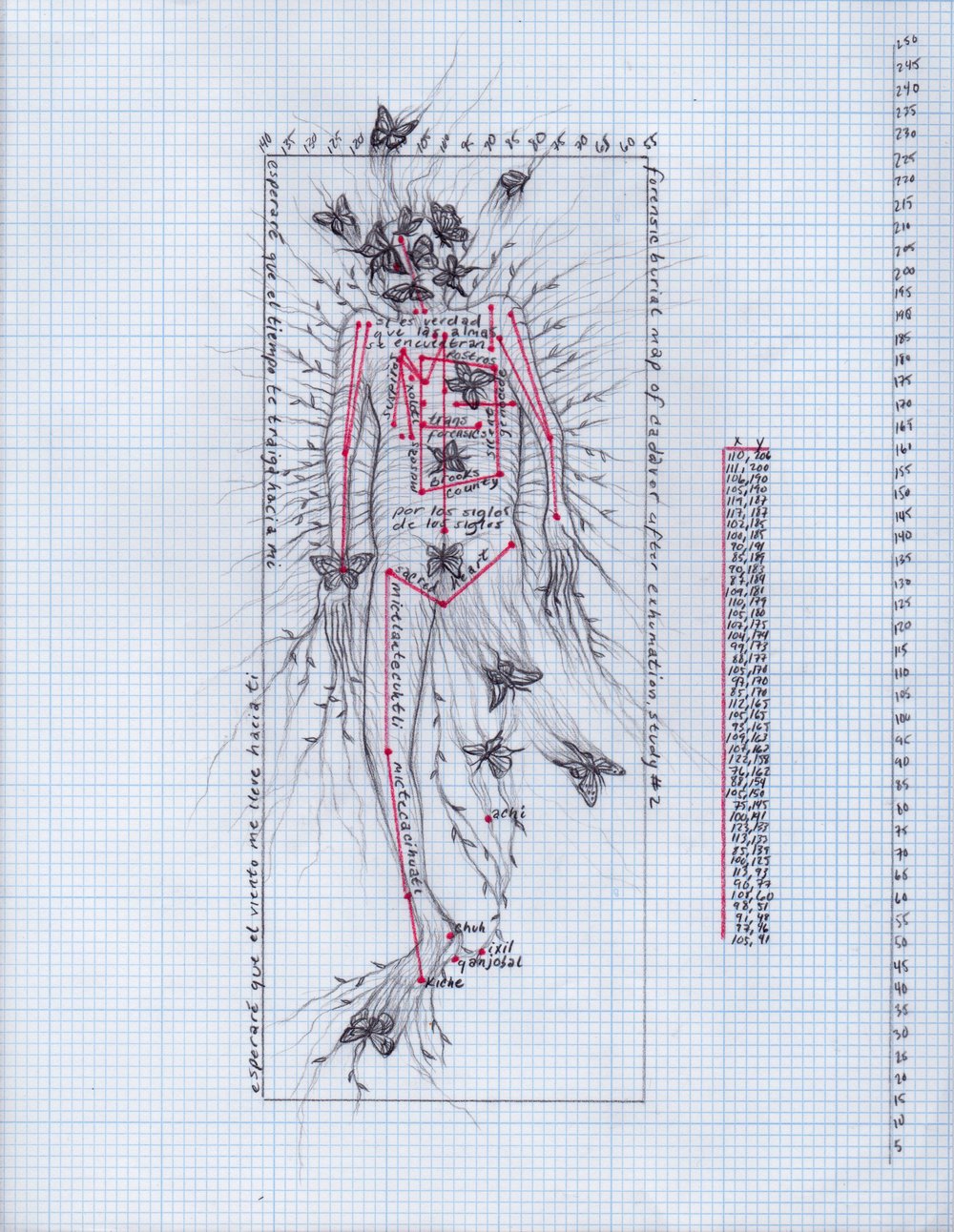

In a series of drawings titled ‘Forensic Burial Maps of Cadavers,’ Angel Lartigue appropriates the practice of forensic anthropology’s gridding of cadavers to depict corpses imbued with fantastic qualities. Corpses of marginalized people are often seen as numbers, lines, and/or metonymic symbols that erase their humanity. Jason De León’s “Hostile Terrain” installation has toe tags represent migrant deaths along the US Mexico border; Coronavirus death numbers obfuscate the high percentage of Black & Brown people that are disproportionately affected by the virus. In these drawings, Lartigue ‘documents’ cadavers’ decay along various planes, including what is not traditionally noted in forensic studies that makes each cadaver part of a larger conversation of nature and history: insects drawn to the corpse stench; the passage of a soul from its mortal container; the constellations formed from different points of maladies; the melding of flesh into dirt & roots; the feathers of vultures; written notes from song lyrics, concepts, and astrological points. Lartigue depicts them all along a grid.

I lived in many apartments throughout my life. In B2, I often drank until I wept myself thirsty. I have no idea what happened in B1 even though only two layers of drywall separated my neighbor and me, until I saw a record player amongst all of their evicted belongings. We’re just passing through boxes in grids we don’t own, after all.

Grids have a power to quantify how much is ‘necessary’ to sustain human life, and their absence or obsolescence can be used even further to oppress, such as the power grid in Puerto Rico and the plumbing of Flint, Michigan. Grids attempt to be anti-narrative, to facilitate information and/or resources within a limited space for interpretation by a power. This is not the case. The grid is an abstraction of reality that places a space outside its history to implement a consciousness. A field of grass can become a home; a burger joint becomes a cash advance agency which turns into a thrift shop until it is bulldozed over for a high rise. A blueprint for a building cannot have feedback from the building itself; POC, who historically have been restrained from having generational capital, can’t either.

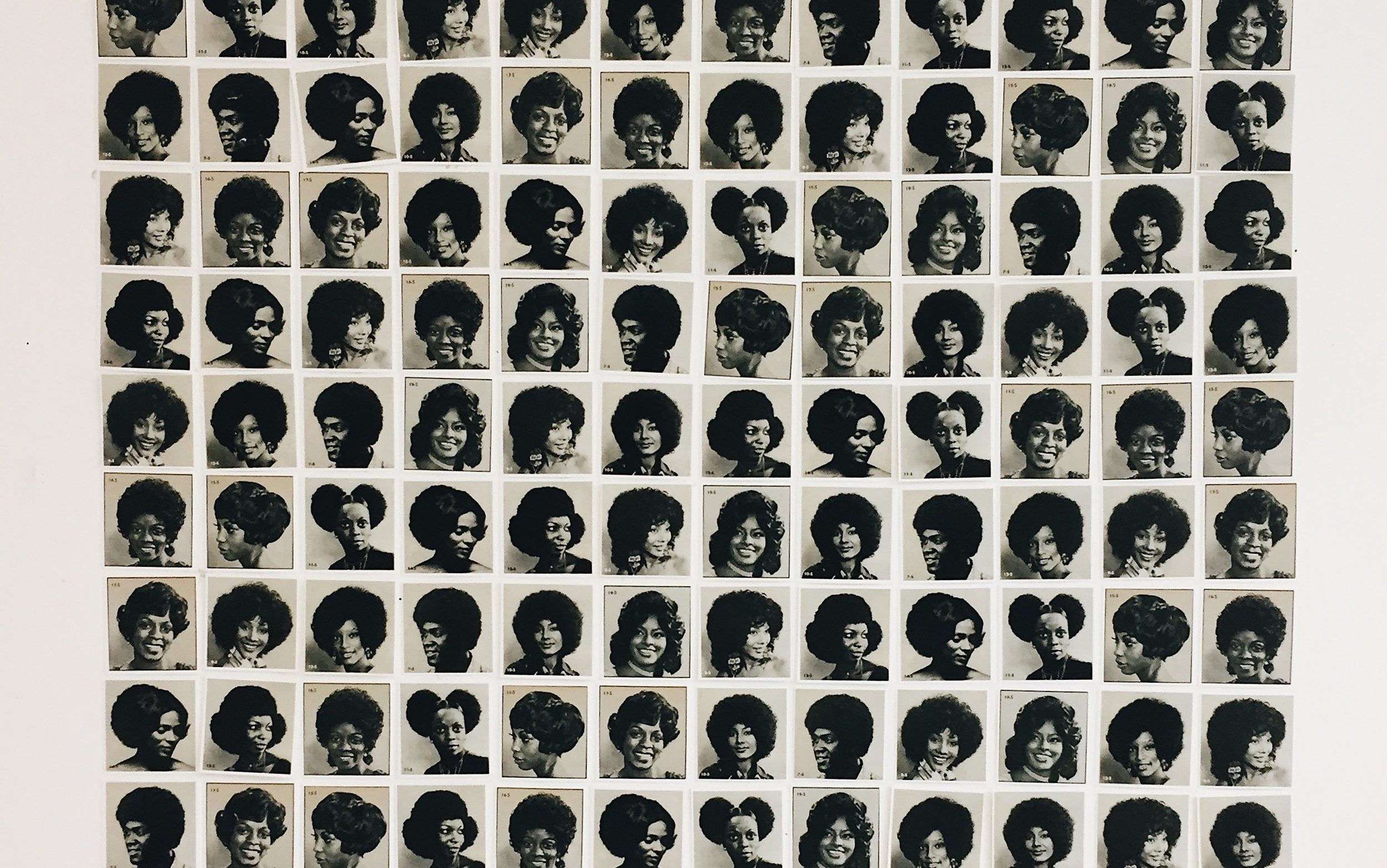

In Irene Reece’s series titled “There Were Always People Like Me,” one piece uses the grid as a saturation of images to counter erasure of Black beauty. Reece places images from 50s/60s advertisements of various Black hair models on a 12’’x12’’ grid. Its purpose is to overwhelm the viewer with depictions of Blackness absent in American conceptions of beauty that often defer to whiteness. Reece notes the “feeling of being brainwashed” but in the opposite direction of prevailing narratives from oppressive white media. The nature of this overwhelming or brainwashing is either empowering or worrying. This brings into question how the mind works when presented with repetitive images of a single narrative. A tool of colonization is repetition: providing singular ideations of abstractions such as beauty, intellect, history, success, aesthetics, etc. Reece uses the grid to subvert generations of colonization in a single piece.

*

Those with the ability to dictate the nature of said grids and cull them to their benefit has mostly been in the hands of white people in America; the self-determination afforded to white, rich people to decide the aspects of a city and who has access to resources has always trumped those of communities of color through racist efforts such as gentrification, redlining, gerrymandering, citizenship documents and forms, etc. It is the forced navigation of grids and the squares within them that has inherently plagued the experience of communities of color: renting apartments rather than owning a home; having a strict file of forms that deem your existence legal in a country; being subject to the erasure of complexity in favor of a simplified structure to fit the needs of an oppressor; and knowing when to break from entrenched patterns of racism that have consistently denied POC’s self-realization. As inhabitants of a shifting metropolis, us Houstonians of color are aware that a square on a grid is a life, that we have to pack as much density of our lives into oppressive structures.

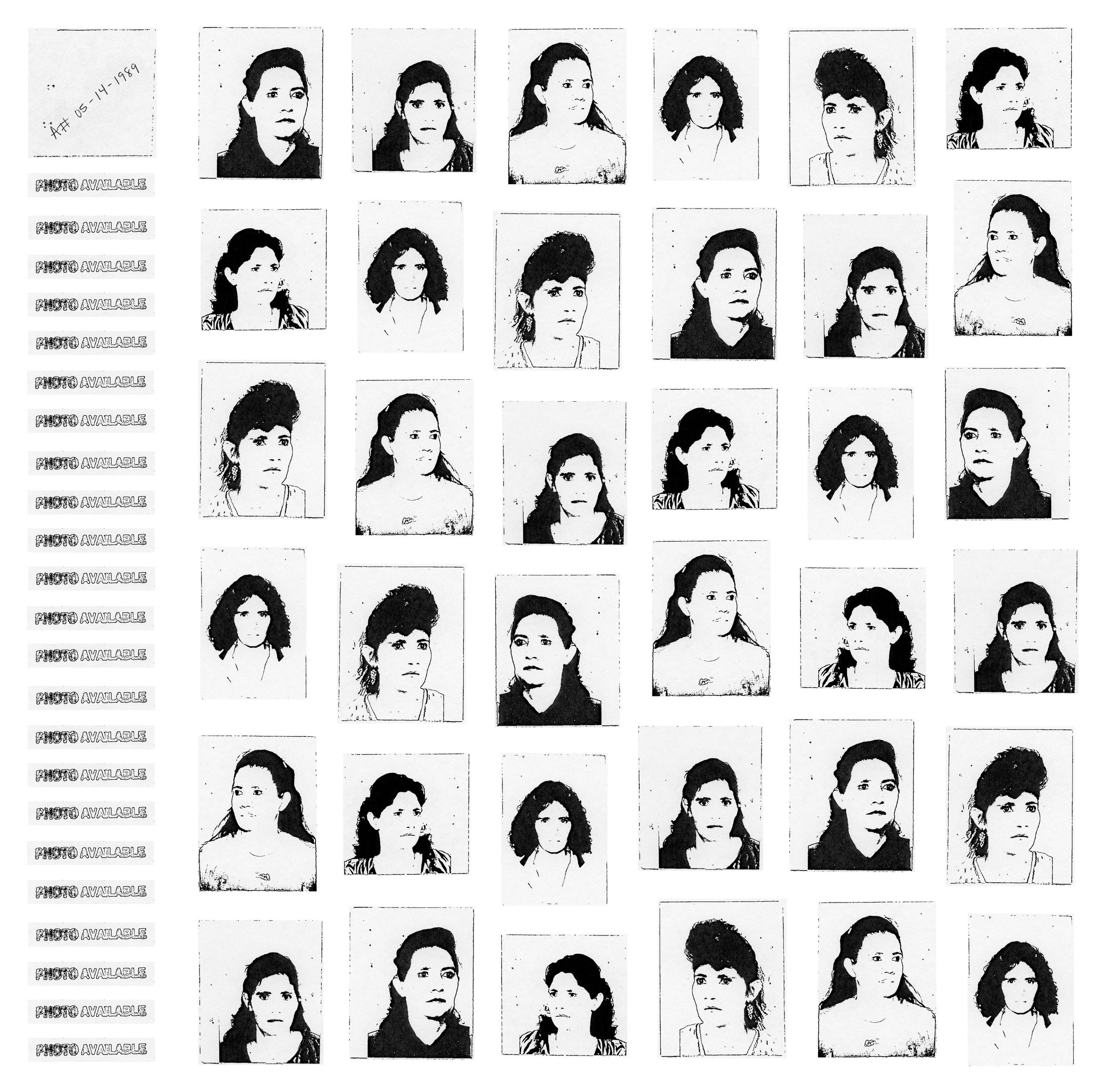

Jessica Gonzalez’s “A#05-14-1989” uses the grid to explore the use of bureaucratic processes to institutionalize people of the Global South through redundant, repetitive documentation. Gonzalez lays out several portraits of her mother, a Salvadoran refugee, taken by the American government at different years for her file, the name of which begins the x-y axis. The American government contributed to the continuation of the Salvadoran Civil War. Each picture is in black and white with a y axis dehumanizingly stating over and over again “PHOTO AVAILABLE,” replicating the sense of process for the sake of process. A documentation for the sake of documentation. If one is documented as living in a country for years, how is a ‘citizen’ any different? Gonzalez use of the grid form reveals that nothing had changed in her mother’s situation, merely that the US government sought a variation in her exile from her country as though looking for an excuse to expel her. The grid is a document of oppression.

*

Through these works, I see a desire to counter the oppressive structure of grids with declarations of control in the hands of POC. Art, then, becomes a way to reappropriate and deny the oppressor’s singular vision of a tool. The master’s tools cannot dismantle the master’s house, but perhaps those same tools can be seized to build another foundation that can facilitate another vision. The grid, it seems, can be seized creatively, at least.

In Marcos Hernandez Chavez’s series of pieces, with various, conceptual titles, made of cotton or silk thread woven through 12’x12’ wood frames with pegs, the grid is revealed to be a paradoxical container of infinity. The seemingly random and chaotic appearance of the threads must be in an order since unraveling them one by one would require a patient, meditative hand. It goes to show the infinite nature of how a life can be fulfilled but is still destined to occur in one setting, a paradox of chance within the rules. We question the nature of free will in a set amount of overlying circumstances, how relative infinity is in the density of a space. The math and what can be quantified vs who finally makes what choice. This is the presence of a consciousness without a consciousness inherent in grids.

1 Daniel Herriges, “How the Government Segregated America’s Cities By Design,” last modified September 26, 2019, https://www.strongtowns.org/journal/2019/9/26/how the-government-segregated-americas-cities-by-design.